|

The 20's for young artists in

Munich were by no means as rosy as was generally

described in accounts of the times. The city,

although owning a rich artistic tradition, was not

particularly open towards avant-garde ideas, to new

forms of expression whether in painting, sculpture

or architecture.

The established, long-standing artistic groups were

not keen to grant exhibition space to new young

talent. Nor could the new wave expect much help from

municipal or state arts bodies. So a small but

enthusiastic band of young artists joined together

in the movement they named Juryfreie with a founding

charter based on mutual friendship and firm

opposition to the entrenched power of the artistic

establishment. Without doubt they saw themselves as

revolutionaries; and they were. At the start of the

1930's anyone interested in meeting these new young

artists and getting to know their work could go to

the exhibition rooms the "Juryfreien" had set up on

the corner of Prinzregenstrasse opposite the Prinz

Carl Palace. Here visitors could see not only

paintings by Juryfreie members but also work by

artists which established galleries (both

state-owned and private) still refused to show.

Abstract and surrealist artists like Albers, Arp,

Baumeister, Brancusi, Max Ernst, Mondrian, Picasso

and Schwitters to name just a few were exhibited for

the first time in Munich thanks to the Juryfreie.

The group also featured work by modern architects

whose designs would otherwise have been ignored. The

movement also organised concerts of contemporary

music featuring the work of composers like Karl

Amadeus Hartmann and Milhaud among others.

Sales of paintings at the exhibitions did not even

cover expenses so the group organised carnival

parties as a way of raising funds. The Juryfreie

parties soon became famous in a city of inveterate

partygoers.

But the fun soon came to an end with the

arrival of Hitler and his brown-shirted

national socialists. They would decide what

was art and what wasn't. The banning of the

Juryfreie movement was part of a broader

cultural attack aimed at destroying

"Bolshevik" cultural organisations.

Juryfreie members could now only paint,

sculpt and make architectural designs in

hiding. If I have described the situation in

which young artists in Munich found

themselves around 1930 and given an outline

of the Juryfreie's activities, it is because

it was at this time and in this situation

that the painter Christian Hess was living

in the Bavarian capital. I first saw his

paintings at a Juryfreie exhibition. It was

at one of the group's parties that I first

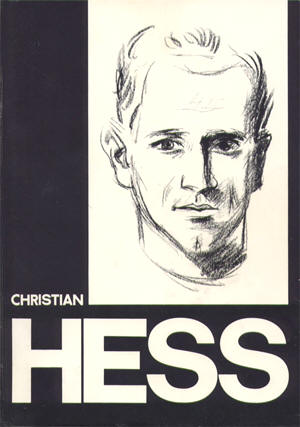

met Hess. He was around 35 with sharp

features and a pleasant, intelligent

expression. He was not very tall, slim and

seemed to possess a typically Bavarian

temperament - but the almost impertinent

openness clearly concealed a deep

sensitivity. I remember at one exhibition on

Prinzregenstrasse I was looking at some

paintings by Joseph Scharl (similar to Van

Gogh) but I was far more struck by the quiet

serene canvasses by Christian Hess which had

been hung alongside. Of all the paintings

which I viewed during that period in Munich

those by Hess are without doubt the ones of

which I maintain the clearest memory. But the fun soon came to an end with the

arrival of Hitler and his brown-shirted

national socialists. They would decide what

was art and what wasn't. The banning of the

Juryfreie movement was part of a broader

cultural attack aimed at destroying

"Bolshevik" cultural organisations.

Juryfreie members could now only paint,

sculpt and make architectural designs in

hiding. If I have described the situation in

which young artists in Munich found

themselves around 1930 and given an outline

of the Juryfreie's activities, it is because

it was at this time and in this situation

that the painter Christian Hess was living

in the Bavarian capital. I first saw his

paintings at a Juryfreie exhibition. It was

at one of the group's parties that I first

met Hess. He was around 35 with sharp

features and a pleasant, intelligent

expression. He was not very tall, slim and

seemed to possess a typically Bavarian

temperament - but the almost impertinent

openness clearly concealed a deep

sensitivity. I remember at one exhibition on

Prinzregenstrasse I was looking at some

paintings by Joseph Scharl (similar to Van

Gogh) but I was far more struck by the quiet

serene canvasses by Christian Hess which had

been hung alongside. Of all the paintings

which I viewed during that period in Munich

those by Hess are without doubt the ones of

which I maintain the clearest memory.

So, when I recently visited Messina and

saw the meticulously curated retrospective of Hess'

paintings, I was able to make my acquaintance once again

with many of his works. There was in no way the sense of

disappointment that sometimes occurs when after decades you

meet an old friend - or an old painting - on the contrary.

Many of the later paintings which I was seeing for the first

time served only to strengthen my previous impressions. The

promise shown by the artist in his early thirties had been

richly fulfilled in his later works. I could not have known

this in 1948 when at a vast exhibition in Munich I saw again

two of Hess' paintings which clearly stood out from the

majority of the works on show for their sheer expressive

power. But by that time, when artists in Germany were once

again able to paint and exhibit their work, Hess was already

dead. He did not have an easy life; perhaps he had not

sought it. Although he did everything well: painting,

drawing, carving puppets, playfully sculpting figures in the

sands on the Baltic coast and modelling with such hard work

and diligence in his studio. He was by no means without

self-criticism and he took his artistic activity far more

seriously than might have seemed to an outsider.

He left the gymnasium early and enrolled in the Innsbruck

State arts and crafts institute where he began painting.

Later he had to work at the Mader

art glass studios in Innsbruck and at the Kuntner ceramic

workshop in Brunico before he was able to begin studying at

the Akademie der Bildenden Künste

in Munich in 1919. Even after he had completed his studies

under Becker Gundhal, Hess had to keep busy in the search to

make some money. In a jeweller in Pforzheim he found not a

patron but a source of commissions for copies of old masters

displayed in museums in Vienna and Florence. Although this

activity hardly served to meet his longing for artistic

affirmation, it is possible to maintain that it did help to

develop and refine his innate sense of colour, shade and

tone. In any case, copying did not lead Hess, as it did

Lenbach, to old-style mannerism. He learned from the old

masters but he reserved the right to find his own way of

expressing form and colour which he found in nature. In the

beginning much of Hess' painting is clearly influenced by

the Munich school. His unflagging enthusiasm for drawing and

painting from nature allowed him to move beyond and find new

freedoms. Above all his long stays in Italy and the summer

he spent in Sicily at his sister's - who had married and

settled in Messina - helped him enormously in the search for

an artistic language in which he could achieve greater

self-expression. In many paintings from 1927 and 1928 there

is a growing sense of colour and an increased precision of

form. The statue of Neptune at Messina, a highly expressive

work by a classicist sculptor, provided the impulse for a

majestic composition in which the real is developed to

almost mythical-allegorical proportions and offers an

element of magical romanticism which in some respects may

remind viewers of De Chirico. Sometimes one may observe a

tendency to overcome form to reach a more expressive

perspective, as in the painting “Ponte di Bracciano” and in

the superbly modelled "Reclining Torso". A group of houses

becomes an abstract composition of red and black cubes.

Emotions found in the paintings of Cezanne are elaborated on

in still lifes of beautiful lyrical reality. In the

landscapes the graduation of colours and tones is majestic.

Towards 1930 the nudes - in drawings and paintings - become

more animated and in the same period there are also still

lifes of clearly abstract construction. For all those who

decades ago saw only a few individual paintings by Christian

Hess this exhibition which brings together his oil paintings

and drawings - unfortunately examples of his plastic art

have almost completely disappeared - offers a first look at

the development of this richly talented artist. All the other artists are present with one work, allowing us

to place Christian Hess clearly among the most interesting

talents to have come out of the rich traditions of the

Munich school in the period between the two wars and follow

new directions.

Hans Eckstein |