|

|

|

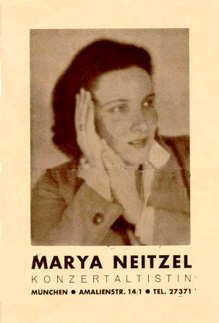

Christian Hess and Marya Neitzel in 1925 |

They

met in the autumn of 1925 at a concert in Munich.

The spark which enflamed Hess’ emotions and left him

spellbound was struck by an aria from Gluck’s opera

Orfeo ed Euridice sung enchantingly by the warmly

expressive mezzosoprano Marya Neitzel. Transported

as she was by the singing, the intimate perfection

of music and poetry so typical of Gluck, Neitzel

instantly struck the artist’s sensibility. Hess was

also smitten by the singer’s undoubted beauty. It

was an extraordinary meeting between two artists who

liked each other at first sight.

Hess is so taken

that a few weeks later, in the middle of December,

he writes to his sister Emma in Messina to tell her

about the meeting with Neitzel. At that time in

Munich Hess is sharing an apartment-studio

with three artist friends (Florian Bosch, Sigfried

Kuhnel and Konig). The atelier is untidy and very

cold and Hess complains to Emma: “… I would like

to receive her in the best possible conditions,

inviting her to a place that is cleaner and more

agreeable. She is the widow of a state functionary

and has three lovely young boys. At the moment she

is working only occasionally as a singer as she is

without a regular contract. She is as tall as me -

and very pretty. She is now in Switzerland, from

where she writes me many letters. If I can earn

enough money to travel to Italy in the spring, she

will come with me - naturally paying her own way.

She gives me a hand for many things and she takes

great concern over me; no bad thing as I’m a

bachelor and disorganised artist.”

|

A concert

performer for Radio Munich |

|

|

|

A brochure featuring the German

mezzosoprano Marya Janke-Neitzel, a

concert performer for Bayerische

Rundfunk, a renowned interpreter of

a vast repetoire ranging from lieder

by Beethoven, to cantatas by

Telemann and operas by Gluck (Orfeo

ed Euridice) and Richard Straus (Ariadne

auf Naxos). Among her teachers was

her brother in law Otto Neitzel, a

celebrated pianist, composer,

conductor and music critic. She

received plaudits for her

appearances at the Berlin Opera and

a series of recitals between the mid

1920’s and 1930’s in theatres and

concert halls across Germany,

Austria and Switzerland was greeted

with rapturous praise. (See

reviews).

She was also a serious student of

popular music and a talented author

of songs for the theatre. From her

collection “Zwei gedruckte

Notenhefte“ the composer Alfred von

Beckerath produced a highly

successful musical play for

children, "Der Schäferreigen", in

1962. |

At the

beginning of February 1926 Hess writes again

from Munich to his sister: “I am in the

new atelier at Schellingstrasse 46. It’s on

the fourth floor, is small and narrow but

comfortable and cheap.” Towards the end

of May he confesses: “The only reason I

stay on is my friend. She is singing at the

Berlin Opera and I hope she’ll be back to

Munich soon. I don’t think I’ll be able to

come to Sicily in the summer.” And on 26

July he writes to Emma: “I’m sitting in

the living-room of my friend’s house at

Amalienstrasse 14; I’ve moved in here. The

apartment is on the first floor. All the

walls are covered with my paintings,

water-colours, drawings and Models. It

is elegant and artistic here. Let’s hope

this marks the beginning of my ‘seven fat

years’.” On 21 August he sends a joyful

letter to his sister: “In the last few

weeks I decided to completely renovate my

friend’s house. It’s been repainted, there

are new carpets, everything’s been scrubbed

and polished.”

Hess is so happy

with Marya and gets on so well with her three

children, he feels the need to become an integral

part of the family. At the beginning of 1927 he

proposes marriage to Marya. She is flattered, but

feels unable to accept for financial reasons. If she

were to marry Hess, she would lose her widow’s war

pension and the allowance for her children. How

would it be possible to survive without the security

offered by this fixed income? They both know only

too well how difficult it can be first to sell a

painting and then how long actually it takes to

receive the money.

Hess is bitterly disappointed. He does not want to

be a burden and he also feels the need for a period

of reflection. He leaves for Sicily, but the

separation only makes his affection for Marya grow

stronger and he returns to Munich. In order to

contribute to the family budget he sells some of his

paintings in installments receiving 100 marks a

month.

|

|

|

The Worthsee with the Zugspitze in the

background |

The sense of

family harmony grows; in the autumn of 1928 Hess

writes to Emma: “I’m with Marya and the boys at

Worthsee. The atmosphere here – the lake, the clouds

– is marvellous. I lounge in the back of the boat

and the boys row me round the lake. Not far away we

can see the Zugspitze; on the summit – around 3,000

meters – it’s two degrees below zero. All around is

the sweet smell of freshly mown grass. Right behind

the house is a wood full with hares, deer, foxes and

owls. Marya takes care of everything with such calm

joy: cooking, cleaning, making the beds, cooking

again - and all the time singing,” Marya added

to the letter: “We’re sitting on our verandah; we

can’t see the Straits [of Messina] but instead the

Worthsee which is heavenly too. With my four men to

look after I’ve got a mountain of work, but here in

the country everything’s easier – although there’s

not much sun.”At the beginning of 1930 Hess

writes from Munich to his sister: “At last I

received the money from the council for my painting.

I paid off some of my debts which left me with 10

marks.” Later that spring Hess was commissioned

to paint a series of frescoes at the spa in Bad

Oeynhausen near Hannover. The job would pay him

2,000 marks. On 4 October the artist writes to Emma:

“Dear sister, I sold the painting I told you

about in Switzerland for 1,000 marks to friends of

the patron and collector Karl Hofer. I’ll be paid in

installments.”

|

|

|

Marya with Hess and his niece

Luisa in Messina, summer 1930 |

A few years later

Hess would be forced to leave Munich because of the

politica tension in the Bavarian capital. Already in

March 1931 he writes to Emma: “A few days ago we

staged a protest at a conference on modern art.

Hartmann and me were thrown out; two other

colleagues were beaten by the SA.” In subsequent

letters to his sister Hess adds: “… I’m very

involved in legal business and am called upon to be

a witness…” and “… the whole political

situation is extremely turbulent. You can’t even

open your mouth to say a word of common sense and

people think you want to enter politics. How I would

love to be in Sicily and hear none of this.”

In the summer of 1931 Hess’ paintings are among a

thousand works destroyed in a massive blaze at the

Glaspalast – a fire that later proved to be arson.

Then the Nazi regime orders the dissolution of the

Juryfreie movement which it accused of being a

Bolshevik organisation. The economic situation is

critical: “In Germany it’s now impossible to make

any kind of living by painting,” Hess writes to

his sister, “Send me some recipes and I’ll work

as a cook. Luckily I’ve got some friends abroad and

I sold two water-colours in Switzerland.”

In a letter dated 19 June 1932 Hess

writes to Emma: “All these continual decrees are

cutting seriously into Marya’s pension. The

children’s allowance stops when they’re 15, but

expenses just keep on rising. I sold a painting; we

spent a third of the money on food and the rest on

coal which we’ll need of course for the winter.”

Simply getting by is more and more difficult, not

least because of the unremitting ostracism towards

artists in the Juryfreie. Hess can stand the regime

no longer and wants to get out of Munich. On 17 July

1933 he sends a postcard to Emma: “I’ve just

bought a train ticket for Messina. It wasn’t cheap.

If I can get a visa, I’ll leave today or tomorrow.”

A week later Hess says goodbye to Marya and the boys

and moves to Sicily where he intends to stay a long

time.

The

birthday

collage

In

the spring of 1934, when he was in exile in Messina,

Hess created a special collage for Marya’s birthday.

He folded it twice, popped it into an envelope and

sent it to Munich so that it would arrive in time

for 24 April – Marya’s 43rd birthday. The collage is

redolent of the couple’s memories of journies and

times spent together: springtime in Sicily – la

dolce vita – love – Marya’s orchestral concerts -

the Bach Gesellschaft – her performances on the

radio. Surrounding the outline of the cloth vase a

spray of faded petals and sprigs mostly made from

thin strips of newspaper covered with sweet

greetings for his beautiful German sweetheart whom

he calls by the pet name of ATA. At the bottom of

the page a flurry of greetings and best wishes from

Sig. Luigi (the painter’s Italianised nickname), his

sister Emma, his brother in law Guglielmo and his

nieces Luisa and Antonia. Thanks to the kind

permission of Frau Leonore Neitzel, in the summer of

2008 the collage was displayed as part of the major

retrospective of Hess’ work at the Rabalderhaus

Museum in Schwaz, the Austrian city where the

artist died in 1944. The same exhibition will be

held from November 2008 to January 2009 at the

Municipal Museum in Bolzano, the city where Hess was

born in 1895. 74 years after it was made the collage

has maintained all its special artistic character –

and its sheen of melancholy. In

the spring of 1934, when he was in exile in Messina,

Hess created a special collage for Marya’s birthday.

He folded it twice, popped it into an envelope and

sent it to Munich so that it would arrive in time

for 24 April – Marya’s 43rd birthday. The collage is

redolent of the couple’s memories of journies and

times spent together: springtime in Sicily – la

dolce vita – love – Marya’s orchestral concerts -

the Bach Gesellschaft – her performances on the

radio. Surrounding the outline of the cloth vase a

spray of faded petals and sprigs mostly made from

thin strips of newspaper covered with sweet

greetings for his beautiful German sweetheart whom

he calls by the pet name of ATA. At the bottom of

the page a flurry of greetings and best wishes from

Sig. Luigi (the painter’s Italianised nickname), his

sister Emma, his brother in law Guglielmo and his

nieces Luisa and Antonia. Thanks to the kind

permission of Frau Leonore Neitzel, in the summer of

2008 the collage was displayed as part of the major

retrospective of Hess’ work at the Rabalderhaus

Museum in Schwaz, the Austrian city where the

artist died in 1944. The same exhibition will be

held from November 2008 to January 2009 at the

Municipal Museum in Bolzano, the city where Hess was

born in 1895. 74 years after it was made the collage

has maintained all its special artistic character –

and its sheen of melancholy.

Marya’s

family decimated by two wars

Marya

was the daughter of Dr Lorenz Janke, a highly

regarded researcher in chemistry and botany

who headed the State Laboratory in Bremen.

Janke loved flowers and designed and tended

an alpine garden that was his pride and joy.

He died aged just 53 in 1906. Marya and her

younger sister Luise were sent by their

mother to the Meon Misail boarding school at

Neuchatel in Switzerland to finish their

education.

Right from childhood Marya

was blessed with a beautiful voice and in

Neuchatel she began singing lessons which

she was to continue in Bavaria. Marya grew

up in the Gauting district of Munich – the

Bavarian capital’s equivalent of Montmartre

– a quarter with a lively and varied

cultural life. She was artistic and

well-read, qualities appreciated by

Professor Walter Georg Neitzel whom she

married in 1913 and bore three sons. A

renowned jurist and diplomat, Neitzel was

fluent in several languages, lectured in

Roman law at Harvard University and acted as

government legal consultant for the German

community in China, a country he visited

several times. He was a high-ranking officer

in the Wermacht during the First World War

and was seriously wounded in fighting in the

forest of Argonne in north-eastern France.

He died of his injuries on 17 December 1918,

just over one month after the Armistice and

six months before the birth of his third

son. The two World Wars were to decimate

Marya’s family. The Great War left her a

widow with three children. She was forced to

abandon her home and move to the village of

Herrsching just outside Munich to stay with

her mother who helped her look after the

children. The Second World War proved even

crueller: all three of her sons saw combat;

two were killed, one - the eldest - survived

but only because he was wounded and sent

back from the front in the final stages of

the conflict.

|

Hess’ last letters |

Letter by Hess, dated 22 October 1944,

sent from Innsbruck to Marya in Munich

|

Hess’ last letter, dated 13 November 1944,

sent from Innsbruck to Marya in Munich.

|

Most likely one of the happiest periods in

Marya’s life was that between the autumn of

1925 and the summer of 1933 when her

friendship with Christian Hess wakened her

intellectual and sentimental affinities.

Once again there was a man in the house who

could spend time with the boys and could

offer paternal affection as they grew up. In

these eight years Marya accompanied Hess on

several of his trips to Italy and his stays

in Sicily. She became close to the painter’s

family and would exchange letters with his

sister Emma, brother in law Guglielmo and

the two nieces Luisa and Antonia, who called

her Aunt Maria.

And when Marya was on concert tours around

Europe Hess often went with her. In the

autumn of 1930 in Zurich Marya introduced

Hess to Cecile Faesy, who would later take

care of selling the artist’s work in

Switzerland. Marya could not have known that

her young friend would also become a rival

for Hess’ affections. When Hess abandoned

the political turmoil of Munich and sought

exile in Sicily, Cecile wrote frequently to

the painter. She was aware that Hess’

separation from Marya had led his feelings

for the singer to wane. Her letters to Hess

became more and more affectionate. Before

the artist moved to Messina he went to

Lucerne and met Cecile to collect some money

from paintings she had sold. She later

followed him to Sicily and on 20 August 1934

the couple were married. Just sixteen months

later, however, they split up. Divorce would

follow.

The bitterness of this brief interlude for

Marya and Hess was far overshadowed by the

tragic events of the war. The couple

resumed contact, exchanging letters marked

by firm friendship. Indeed, a few weeks

before Hess died from injuries received in

an allied air-raid on Innsbruck the last two

letters he ever wrote were to Marya. The

content was dominated by the war: the deaths

of common friends and acquaintances, Marya’s

concern for her son Walter, missing in

action. In one of the letters Hess includes

a sketch of himself in hospital – almost

certainly the last drawing he ever made. In

his final letter Hess recounts the air-raid

of 20 October 1944 and the anguish of being

abandoned among the rubble by a supposed

friend. In 2002 Hess’ last two letters were

donated to the Tirolerlandesmuseum

“Ferdinandeum” in Innsbruck by Frau Leonore

Neitzel, the widow of Wolfgang, Marya’s

first son and the only one of her children

who survived the war.

|