|

Uncovering themes in three of Hess’ painting |

||||||||

|

(d.m.a.) -

Studies on the work and thought of Christian Hess begun in 2008 by

young researchers working outside mainstream academic circles have

led to some surprising discoveries, including the uncovering of the

conceptual themes of three paintings (“The Fortune-teller”,

“Suggestion” and “Head and hand”) that critics had previously failed

to decipher. These discoveries are the result of meticulous study

which took into account a range of factors, including external

influences, the historical situation, Hess’ personal experiences and

what he intended to express with these three works. These latest

interpretations demonstrate that interest in the life and work of

Christian Hess is by no means dead and indeed continues to spread

far and near thanks to the

Association’s website, confirming still further the continuing

relevance of his work. |

||||||||

|

“The Fortune-teller”: an autobiographical self-portrait |

||||||||

|

Without doubt the most important revelation is that made in March 2009 by the researcher and essayist Cristina Martinelli. After visiting the Hess retrospective at the Municipal Museum in the artist’s birthplace of Bolzano, Martinelli decided to look more deeply into certain aspects of Hess’ career. She investigated a large range of archive material – including that available on this website – and found enough evidence to lead her to believe that “The Fortune-teller” (1933) should be seen as an “autobiographical self-portrait”. In the painting the central figure, who closely resembles Hess, has his back turned to the sea, expressing all the sadness of his Sicilian exile; a sadness which is lightened, however, by the simple kindness of the local people surrrounding him. Dressed as the “fortune-teller”, he expresses his need to pose questions about the future. Another emblematic detail is that the central figure is wearing the red and white striped t-shirt habitually worn by the young artists of the Munich-based Juryfreie movement – a symbol of his isolation from the group. Many of the Juryfreie paintings were destroyed in a mysterious blaze at the Glaspalast in Munich and the group was later banned by the Nazi regime. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

“The Anti-face” - portrait of the soul |

||||||||

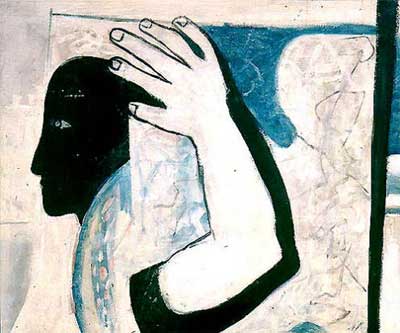

No

less important is the research carried out into Hess’ disquieting

1932 picture “Head and hand”. In the same year, Hess wrote from

Munich to his sister in Messina: “The prospects for the future are

not good, neither politically nor economically.” The painting has

been the object of intensive analysis by the student of comparative

theology Michele Steinfl, and the subject of his essay entitled “The

Anti-face”. Steinfl considers the painting represents a “portrait of

the soul” through which the artist makes available - to those

prepared to look closely and questioningly - his internal struggles

during the months leading up to his voluntary exile in Sicily. “The

anti-face is hidden in obscurity because socratically speaking it

‘does not know’ … it ‘does not know itself’,” explains Steinfl. “And

biblically speaking it does not recognise this ‘itself’ which it

carries within its own heart as the place of residence of that which

is Created.” No

less important is the research carried out into Hess’ disquieting

1932 picture “Head and hand”. In the same year, Hess wrote from

Munich to his sister in Messina: “The prospects for the future are

not good, neither politically nor economically.” The painting has

been the object of intensive analysis by the student of comparative

theology Michele Steinfl, and the subject of his essay entitled “The

Anti-face”. Steinfl considers the painting represents a “portrait of

the soul” through which the artist makes available - to those

prepared to look closely and questioningly - his internal struggles

during the months leading up to his voluntary exile in Sicily. “The

anti-face is hidden in obscurity because socratically speaking it

‘does not know’ … it ‘does not know itself’,” explains Steinfl. “And

biblically speaking it does not recognise this ‘itself’ which it

carries within its own heart as the place of residence of that which

is Created.” |

||||||||

| The Essay by Michele Steinfl | ||||||||

|

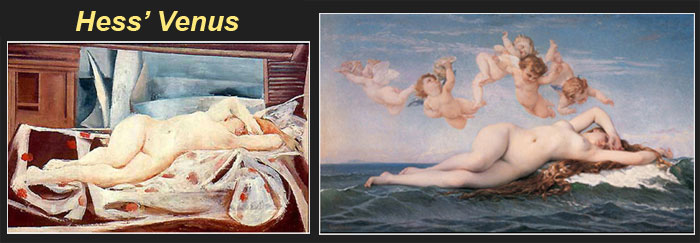

“Suggestion” and “The Birth of Venus" |

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Cristiana Vignatelli-Bruni’s degree thesis (p. 76) | ||||||||